Executive Summary

SG/2009/21

Scottish Government Criminal Justice Directorate

Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers

June 2009

ISBN 978 0 7559 8030 7

This document is also available in pdf format (472k)

Contents

Letter to the Scottish Ministers

Chapter 3 Summary of Inspections Undertaken 2008-2009

Chapter 4 Review of the Prison Inspectorate's Year 2008-2009

Previous Reports

1981 - Cmnd 8619

1982 - Cmnd 9035

1983 - Cmnd 9401

1984 - Cmnd 9636

1985 - Cmnd 9909

1986 - Cm 260

1987 - Cm 541

1988 - Cm 725

1989 - Cm 1380

1990 - Cm 1658

1991 - Cm 2072

1992 - Cm 2348

1993 - Cm 2648

1994 - Cm 2938

1995 - Cm 3314

1996 - Cm 3726

1997 - Cm 4032

1998 - Cm 4428 SE/1999/21

1999 - Cm 4824 SE/2000/71

2000 - SE/2001/227

2000 - SE/2000/71

2001 - SE/2001/227

2002 - SE/2002/191

2003 - SE/2003/287

2004 - SE/2004/207

2005 - SE/2005/175

2006 - SE/2006/198

2007 - SE/2007/183

2008 - SE/2008/162

Letter to the Scottish Ministers

To the Scottish Ministers

I have the honour to submit my seventh, and final, Annual Report to the Scottish Parliament.

ANDREW R C McLELLAN

HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland

4 March 2009

1. Overview 2002-2009

Does it do them any good?

Should the experience of imprisonment do prisoners good? The answer is not as obvious as it sounds. Some will answer that imprisonment should do harm to the person imprisoned, and that pain, whether physical, mental or spiritual, is a necessary and desirable ingredient of punishment. The point is illustrated by the cries of outrage in the press when it was discovered (November 2008) that prisoners in the new prison at Addiewell would actually have their own showers in their own cells (interestingly, when the new block at HMP Edinburgh was opened a few weeks later with the same provision there was hardly any reaction; unlike Addiewell, Edinburgh is a public prison).

Others will answer that it is so unlikely that imprisonment will bring benefit to the prisoner that the goal is not worth pursuing. Every single Annual Report in the last six years has emphasised the damage done to our prisons by overcrowding: nothing suffers more in an overcrowded prison than the attempt to help prisoners change their lives for the better.

Add to that the damage that imprisonment does to family ties and employment prospects and self-respect and addiction habits and to keeping away from the wrong company and it is easy to understand why even the best efforts of prison staff are likely to have only a limited effect. In a famous sentence a Home Office Report in 1990 claimed that "Imprisonment is an expensive way of making bad people worse" (Crime Justice and Protecting the Public, HMSO 1990).

An American Judge, Dennis Challeen, said:

We want them to have self-worth

So we destroy their self-worth

We want them to be responsible

So we take away all responsibility

We want them to be positive and constructive

So we degrade them and make them useless

We want them to be trustworthy

So we put them where there is no trust

We want them to be non-violent

So we put them where violence is all around them

We want them to be kind and loving people

So we subject them to hatred and cruelty

We want them to quit being the tough guy

So we put them where the tough guy is respected

We want them to quit hanging around losers

So we put all the losers in the state under one roof

No doubt he was describing his own country, but it is not completely unrecognisable here.

Nevertheless, the answer to the question "should the experience of imprisonment do prisoners good?" is "yes". There are at least three reasons for the answer "yes". Imprisonment should help to make Scotland safer. This is at the moment a distant goal. After some years of government emphasis on the importance of reducing reoffending 87% of the population of Polmont Young Offenders Institution have been there before their present sentence. If the behaviour of convicted people does not change more and more crimes will be committed.

The second reason that the experience of imprisonment should do prisoners good is that their turning from a life of crime to a useful life in society saves much public money. Prison is very expensive. The rebuilding in the last few years of HMP Edinburgh cost £120 million. The annual cost of imprisonment in Scotland has been £280 million (even before hidden costs like child care for the families of imprisoned parents are taken into account). That works out at £110 per day per prisoner (Alex Spencer, Scottish Consortium on Crime and Criminal Justice, 2007).

The third reason is summed up in a sentence used often about prisoners by Kenny MacAskill, Cabinet Secretary for Justice: "they are not 'them', they are 'us'". Healthy societies recognise that everyone belongs together and that excluding some diminishes all.

Seven good years

The biggest single difference in Scotland's prisons in the last seven years has been the transformation in the living conditions of prisoners. This transformation is not yet complete; but it has been remarkable. My earliest reports make comments like " the conditions in 'C' Hall (Perth) are dreadful; and conditions in Argyll and Spey Halls (Polmont) are very bad." Recent reports, on the other hand, say " It provides a much improved standard of cell, furniture and toilet access… these better conditions are good for prisoners and also help to improve the working environment for staff (Glenochil)."

The change is the result of a huge building programme since 2002. It has produced one completely new prison at Addiewell (opened December 2008) and four almost completely new prisons at Polmont, Edinburgh, Perth and Glenochil. The new style is to build very large halls holding more than 300 prisoners. These halls may not be designed to produce the best possible interaction between staff and prisoners, they are noisy, and the temperature is sometimes very difficult to control. But they are very much better than what was there before.

New building work is also producing first-class "facility" buildings. The workshops, gym, prisoner reception area and health centre at Edinburgh Prison, for example, are quite exceptional. The visit room at Glenochil is splendid. The whole of Addiewell Prison is new; and its "academy" facilities match the very high standard of its living accommodation.

Unfortunately, it still cannot be said that all prisoners live in civilised accommodation. As long as prisoners in Peterhead have to endure their own form of slopping out our prisons are not yet decent. The Scottish Government has indicated that a replacement for HMP Peterhead is planned.

As important as the improvement in living conditions, although not so immediately obvious, is the improvement in the safety of Scotland's prisons. The statistical evidence is clear. The number of serious assaults is much lower than it used to be. The evidence from prisoners is equally clear. Even seven years ago prisoners would normally speak in prisoner groups of feeling unsafe: now it happens rarely. On my early inspections the sight of prison officers running to respond to an alarm was quite familiar: not now. Making prisons safer is important both for prisoners but also for prison staff: how seldom do the Scottish public think about prison staff and about the implications for them (and their families) of what happens in our prisons.

The improvement in safety is all the more welcome and all the more surprising since it comes at a time of unprecedented overcrowding. I shall have more to say about overcrowding; but I have often said that it is likely to make prisons less safe. There are two reasons at least why this has not happened.

One is the installation of cameras throughout prisons. Cameras have been, in my experience, universally welcomed by prisoners as a significant contribution to their own safety.

The other reason for improvement in prison safety is the good relationship which exists between prison staff and prisoners. In my Annual Report for 2005-2006 I wrote of "the most surprising fact": it is always, without exception, the fact which most astonishes people who are not familiar with prisons. It is a figure found in the SPS Prisoner Survey. The survey is by no means an anodyne exercise in which prisoners merely provide the answers which they think might be hoped for. In a question about the standard of healthcare, for example only 55% of prisoners in the 2005 survey were positive. In a series of questions about food between 8% and 24% commented that various aspects of the catering process were "very bad". So against a background of fairly critical assessments by prisoners the answer given to the question about relationships with prison staff is nothing short of astonishing. To the question "How do you rate relationships with staff in your prison?" the number of prisoners who replied "ok or better" was 97%. Only three prisoners out of 100 feel that they are not properly treated by prison staff.

When I took up this appointment I had a vague notion that it would be good to bring some humanity into the brutality which I guessed would be the mark of the treatment of prisoners by prison staff. I was very wrong. I have constantly been humbled and inspired by the patience and humanity and fundamental decency which I have consistently found in Scotland's prison staff at all levels. This is all the more remarkable when it is recognised that they are dealing daily with some people who are the most difficult and dangerous in the country. One of the stories I treasure is of the prisoner who asked his hall manager to be best man at his wedding!

Not all prison staff always meet the highest standards; and it is essential that the Inspectorate is vigilant, and the SPS is vigilant, in the matter. Good relationships does not mean "being nice to prisoners": often the best relationship with a prisoner will be a challenging one. But experienced prison people (staff and prisoners alike) often speak of the transformation in the treatment of prisoners which Scotland has seen in the last 30 years: a transformation entirely for the better.

I welcome this transformation not least for the increased safety it offers to prison staff in their working environment. To work in a prison, however, can never be completely risk free, and it would be foolish to assume that good relationships guarantee that prisons will never be disturbed and violent. We should be proud in Scotland of the work done by prison staff on our behalf; and we should be proud of the good relationships which exist in our prisons.

Two other factors deserve attention for their contribution to prison safety. The comprehensive anti-suicide procedure first introduced in 1997 was updated in September 2005. Any suicide is a tragedy and a suicide in prison always affects prisoners and staff deeply. The new procedure followed a very difficult time in the 1990s when the number of prison suicides made headlines. The number has reduced significantly. Two aspects of the new procedure have been particularly significant. One is the strict risk assessment system, and the other is the careful training of all prison staff. The operation of anti-suicide arrangements is always an important part of prison inspections.

It was in Barlinnie that inspectors first reported on a well-developed First Night Centre. Imprisonment can be terrifying; and particularly terrifying when the number admitted is very high. On most Monday nights there are about 120 people admitted to Barlinnie alone. The initiative of the First Night Centre, and the commitment of the staff to its operation, makes it considerably less likely that a new prisoner will be lost in the crowd. All prisoners are admitted to a dedicated part of the prison, where trained staff take them through a programme of information and answer questions. The report on Barlinnie said " it is difficult to overestimate the difference this initiative has made… The First Night Centre is designed to make introduction to prison life as safe, reassuring and straightforward as possible..." First Night Centres are beginning to appear in other prisons and other prisons are made more safe as a result.

Among the most controversial aspects of imprisonment in the last seven years has been the introduction of the escorting of prisoners by a private company. The Inspectorate has developed systems to address this new aspect of the treatment and conditions of prisoners. It is a remarkably complex business to transport prisoners all over Scotland to courts and hospitals and funerals and Children's Hearings and other places. The arrangement works much better than most people expected. There was some surprise in the media when we presented the evidence that the vast majority of prisoner escorts are carried out properly and effectively; and that prisoners are treated well during escorts.

There are, nevertheless, incidents of lateness and of long journeys in uncomfortable vehicles. The least satisfactory aspect of the escorting of prisoners has been the handcuffing of women, and of women on hospital visits and about to give birth. This indefensible practice has been a scandal.

Two matters mentioned in the overview of 2008-2009 cannot be overlooked here. One of the best days for the Inspectorate was the day on which the Cabinet Secretary for Justice announced that he would bring forward legislation to end the imprisonment of children. I was shocked when I discovered a 14-year-old in Polmont: and the Scottish public (and the Press) were shocked as well. Since then I have taken every opportunity to repeat that prison is no place for a child. Very seldom does anyone disagree.

The McLeish Commission (The Scottish Prisons Commission) published its report on 1 July 2008. All of its recommendations were based on one simple, serious, momentous claim: " High prison populations do not reduce crime. They are more likely to create pressures that drive reoffending than to reduce it." Mr McLeish went on to argue: " Scotland has one possible future where its prisons hold only serious offenders, prison staff regularly and expertly deliver programmes that can affect change and there is a widely used and respected system of community-based sentences. There is another possible future, one in which there are many more prisons, as overcrowded as those today. Dedicated and skilled professionals lack support and suffer from low morale, the public's distrust of the criminal justice system reaches record levels and fragile communities are ignored. We have to make a choice between these two futures."

The Commission aspires to halve prison numbers in Scotland. The change which that would bring to our prisons would be breathtaking. Our prisons would, for the first time in a generation, be able to do what we want them to do. We will ignore the opportunity offered by the recommendations of the McLeish Commission at our peril. Literally at our peril, for, as I have said so often, overcrowded prisons make Scotland more dangerous.

Seven bad years

Nothing I have said in the last seven years has received as much attention as "The Nine Evils of Overcrowding". This was an attempt to describe the damage done.

- It increases the number of prisoners managed by prison staff who, as a result, have less time to devote to screening prisoners for self-harm or suicide, prisoners with mental health problems and prisoners who are potentially violent. Risk assessments will inevitably suffer.

- It increases the availability of drugs since there are more people who want drugs and prison staff have less time to search.

- It increases the likelihood of cell-sharing: two people, often complete strangers, are required to live in very close proximity. This will involve another person who may have a history of violence and of whose medical and mental health history the prisoner will know nothing; and it will involve sharing a toilet within the cell.

- It increases noise and tension.

- It makes it likely that prisoners will have less access to staff; and that they will find that those staff to whom they do have access will have less time to deal with them.

- The resources in prison will be more stretched, so prisoners will have less access to programmes, education, training, work etc.

- Facilities will also be more stretched, so that laundry will be done less often and food quality will deteriorate.

- Prisoners will spend more time in cell.

- Family contact and visits will be restricted.

I might have spent more care on its composition had I known how often it would be repeated. Some of the details could be improved, but the central message is clear. Overcrowding makes everything worse for everyone. Overcrowding certainly makes things worse for prisoners: being locked up in shared cells with sometimes unpleasant, possibly dangerous, strangers for 21 hours out of 24, day after day, month after month, is not likely to promote civilising habits. It makes things worse for prison staff: more prisoners means less time, more stress, more tension. It makes things worse for society: in overcrowded prisons very little can be done to help prisoners to change their lives. There is always someone ahead of you in the queue for the training you need. As a result prisoners are released in the same frame of mind in which they entered prison - or worse. That is no way to build a safer Scotland.

From first to last in inspection reports I have objected to the miserable little cubicles in which prisoners are held in some prisons when they arrive from court. An Inspection Report on Barlinnie in 2003 said: " Reception is the first experience a new prisoner will have of the prison, and the conditions in Barlinnie are not good. Having had their identities checked, new admissions are then locked in cubicles. These are essentially cupboards with a bench seat, observation window in the door and no amenities. They are also dirty: with graffiti on the walls and cigarette ends and food remains on the floors and benches. They are universally referred to as "dog-boxes". Individuals will spend varying periods of time - sometimes two to three hours - locked in these cubicles. At peak times, it is not uncommon for two prisoners to be located in one cubicle. At times there will be occasions when three prisoners may be held. There is not sufficient room for more than one person to sit down. In common with other prisons in Scotland, over 80% of admissions present with evidence of drug misuse. Many will be in poor physical shape and, having lived chaotically, may have a range of health and hygiene issues."

In the last six years almost nothing has changed.

There is only one aspect of accommodation for prisoners which is worse than these dreadful cubicles. Even worse than the cubicles is slopping out. Throughout the last seven years nothing has given me more pleasure than to be able to report "slopping out has ended at Barlinnie", "slopping out has ended at Perth", "slopping out has ended - at last - at Polmont". It was possible at the same time to say "Glasgow is now a more decent city", "Perth is now a more decent city", "Scotland is now a more decent country". Wherever slopping out ended inspection reports reflected not just better living conditions for prisoners but also better working conditions for staff. The reports also reflected improved attitudes among prisoners and better morale among staff.

It is therefore with despondency that I come to the end of my term as Chief Inspector without being able to welcome the total abolition of slopping out in Scotland (it ended in England years ago). Prisoners in Peterhead still do not have proper access to proper sanitation. The form of slopping out used there is believed by some to be not quite as disgusting as the form which was used in other prisons, but it is still awful. The report published in 2008 said " Some steps have been taken to try to alleviate the impact of slopping out, but its continuation at Peterhead remains the worst single feature of prisons in Scotland. It is quite lamentable that the words written in the inspection report of 2006 can be written without alteration today. Many reports welcome the improvement of living conditions in prison after prison: but certainly there is no such improvement in Peterhead."

There are two other groups of prisoners whose toilet provision is unacceptable. Many prisoners live in cells with uncovered, unenclosed toilets (including nearly everyone in HMP Shotts). Many of them who have to eat in their cells have described it as "having all your meals in a toilet". The Report on Cornton Vale published in 2007 repeated what every report I have published on Cornton Vale has said: In some parts of the prison access to toilets during the night continues to cause upset and difficulty. This is because the electronic locking system limits access to the toilet to one cell at a time. It could be possible for a woman to have to wait for an hour after pressing her bell before she will be given access to the toilet. This is far too long, and some women resort to using their sinks. The report on Young Offenders in Cornton Vale published in 2009 says the same thing. It is impossible to understand why this cannot be fixed. It is a humiliation.

Many of the most unhappy features of Scotland's prisons have been criticised repeatedly in inspection reports. Another example is the amount of time spent by prisoners locked in cell. Two years ago I wrote Report after Report tells the same grim story. The law requires prisoners to work. The public expects prisoners to work. Yet in nearly every prison many prisoners are not working. When they should be working - indeed, often when they want to work - there is no work for them. When prisoners are not working they are almost invariably locked in their cells. A useful working day for a prisoner could make such a difference. It could teach good habits of punctuality and self-discipline. It could be a training opportunity to develop a skill to help with employment on release. It could transform the self-respect of prisoners who had never done a decent day's work in their lives and never made anything useful or beautiful. It could keep the minds of prisoners focused on things that are valuable rather than on things that are destructive. It is no surprise that the public expects prisoners to work. But the reality is that prisoners - many of them - spend the working day lying in bed. Usually this is not about laziness: usually it is about overcrowding. In an overcrowded prison there is always someone ahead of you in the queue for work.

Wherever there is a story of a workshop closed, whenever there is a visit to an empty workshop, whenever another member of staff is taken away from training prisoners to provide essential duties elsewhere, there is an opportunity missed and there are prisoners less well equipped than they should be for returning to society and making a useful contribution. Nothing would better equip Scottish prisons for the task of rehabilitation than the daily provision of useful, stimulating, demanding, hard work for every prisoner. Nothing does more harm to prisoners' prospects of law-abiding living on release than lying in bed all day, all week, even all year, doing absolutely nothing.

The people who suffer most from enforced indolence in prison are prisoners on remand. Their numbers have increased very considerably. Their circumstances, meanwhile, have been steadily changing for the worse. It used to be that the Scottish Prison Service tried to provide the best living conditions for remand prisoners. That was a praiseworthy aim: most of them have not been convicted and deserve to be treated as "innocent until proved guilty". But remand prisoners, perhaps more than anyone, are victims of prison overcrowding. Far from the best arrangements in prisons, almost universally now they live in the worst conditions and have the most empty daily routine. Most remand prisoners in most Scottish jails spend more than 20 hours per day locked up in a cell shared with another prisoner. Invariably groups of remand prisoners are the most angry and negative of any groups of prisoners met during an inspection. Yet surely fairness, recognising their legal status, demands that they should receive the best, rather than the worst, conditions and treatment.

There is another example of those who should receive the best receiving the worst. Despite all the efforts of the Scottish Prison Service, sex offenders receive the worst preparation for release. Yet, without doubt, they are the prisoners of whom the public is most afraid. They are those whom the public would expect to receive the best preparation for release. The view that they receive the worst preparation for release is sometimes challenged on the basis that much good work is done in prison with sex offenders, which is true. But the situation is clear. The primary tool used by the Scottish Prison Service to address the offending behaviour of sex offenders is the Sex Offender Treatment Programme. For those convicted of the most serious crimes, serving long sentences, the number of spaces available on the programme is too small - even for those who are eligible for the programme. Many of these most serious sex offenders will not sign up for the programme, since they do not admit their offence. Only a relatively small proportion, therefore, of long-term sex offenders will have completed the Sex Offender Treatment Programme before they are released.

Equally disturbing is the fact that there is very little statistical evidence in the UK that the Sex Offender Treatment Programme makes a difference. There are certainly prison staff and psychologists and prisoners who tell impressive stories about individuals whose lives have been changed; but it is surely time that research evidence was produced to support a programme which remains the principal resource for addressing the offending behaviour of sex offenders in Scottish prisons.

The over-riding reason for the assertion that sex offenders receive the worst preparation for release is not merely, however, to do with the large number who do not participate in the Sex Offender Treatment Programme. It is to do with the absence of any real testing in the community before release. A cornerstone of the preparation for release of the most serious offenders is that they participate in a pattern of community placements and home leaves and open prison, as their responsibility for their own actions is tested in increasing degrees of freedom before release. When they are released they have been carefully tested. That almost never happens with sex offenders. They are nearly all released, untested, directly from closed conditions into freedom. The Report on the Open Estate Inspection published in 2009 found only two sex offenders in the Open Estate and made the point: " Of course it is difficult and dangerous and controversial to give any form of access to the community to imprisoned sex offenders. But it is more difficult and more dangerous, and it should be more controversial, to return them to the community at the end of their sentences without any previous testing in the community and without proper preparation for release."

Seven years of frustration

It is clear that many of the problems faced in our prisons are long-standing problems; and many of them are not any nearer to solution. Why does it take so long for some things to improve? Let me suggest four reasons.

The most intractable feature of prisons is the bad state prisoners are in when they arrive in prison. Bad physical health, bad mental health, bad educational attainment, bad employment record, bad addiction history, bad family support, bad self-esteem, bad company, bad criminal record. That is the typical picture of a prisoner arriving at the prison gate to start a sentence. Over three-quarters of all prisoners have been using illegal drugs immediately before imprisonment. In surveys published by the Governor of Barlinnie recently the proportion of Young Offenders who stated that they get "drunk daily" rose from 7.3% (1979) to 22.6% (1996) to 40.1% (2007). Over half of young men in Polmont have served five or more prison sentences. I hardly ever meet a prisoner who has passed any school examination qualification. It is so very difficult for prison staff to overcome the difficulties which prisoners bring with them into jail. No wonder any small improvements take a long time. I have said so often that it is naïve to blame prisons because they cannot solve the problems of Scotland.

Secondly, allied to that and equally important is the mess to which prisoners so often return when they leave prison. It is shocking, but it does happen, that a prisoner will leave prison with nowhere to live. A television programme about Polmont showed the liberation of a young man who had done well inside Polmont and had tried hard to deal with his alcohol addiction. Within hours of his release his friends had bought him a good deal of "welcome back" alcohol: almost instantly the old patterns re-asserted themselves and very soon he was arriving again at the gate of Polmont. Links Centres, Throughcare, Integrated Case Management, are all signs of the importance which is attached to making good links with the community on release and are welcome and necessary. But the prospects of most prisoners on release are still bleak. Hardly any prisoner walks out of prison into a job. And unemployment, for an ex-prisoner, is often the high road into re-offending.

Thirdly, the damage done by overcrowding has already been emphasised. But it cannot be emphasised too often. Prisons do not improve more quickly because the best efforts of all the most imaginative and caring staff are completely frustrated by the evil of overcrowding.

Fourthly, there is no agreement about the purpose of prisons. There is little political consensus and no public consensus. So improvement means different things to different people. "If you don't know where you are going, any road will take you there."

Seven years of inspecting

The inspection process has developed during the last seven years. The publication by the Inspectorate of "Standards used in the Inspection of Prisons in Scotland", was a turning point. The publication of standards is a reassurance to Scottish Ministers and to the public that the inspection of prisons is consistent, fair and transparent. Independent inspection is concerned not only with what is possible but also with what is right. The standards used in Scotland are firmly based on international treaties and conventions. The idea which guides these Standards is Article 10 of the UN International covenant on Civil and Political Rights: All persons deprived of their liberty shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person.

Nine outcomes are identified in these standards:

- Appropriate steps are taken to ensure that prisoners are protected from harm by themselves and others.

- Prisoners are treated with respect for their dignity while being escorted to and from prison, in prison and while under escort in any location.

- Prisoners are held in conditions that provide the basic necessities of life and health, including adequate air, light, water, exercise in the fresh air, food, bedding and clothing.

- Prisoners are treated with respect by prison staff.

- Good contact with family and friends is maintained.

- Prisoners' entitlements are accorded to them in all circumstances without their facing difficulty.

- Prisoners take part in activities that educate, develop skills and personal qualities and prepare them for life outside prison.

- Healthcare is provided to the same standard as in the community outside prison, available in response to need, with a full range of preventive services, promoting continuity with health services outside prison.

- Appropriate steps are taken to ensure that prisoners are reintegrated safely into the community and where possible into a situation less likely to lead to further crime.

These standards are now used constantly and consistently before, during and after every inspection.

After some years when no thematic inspections were carried out, recently three have been undertaken. Two of these have been published: Learning, Skills and Employability: A Review of Good Practice in Scottish Prisons (2008) - with HM Inspectorate of Education; and Out of Sight: Severe and Enduring Mental Health Problems in Scotland's Prisons (2008).

A third, on the management of High Risk Offenders, is expected later in 2009.

Advocates of good practice in inspection have recently been drawing attention to the value of self-assessment and to the good practice of inspecting most where there is most need, rather than on a merely cyclical basis. These very emphases have been central to the work of HMIP for some time: and it is gratifying to find their value more widely recognised.

The law provides for unannounced inspections of prisons, but I had not undertaken one until 2008. Since that first one in Inverness another one has been carried out in Edinburgh. Inspectors were greeted with helpfulness and courtesy by prison staff in both cases. Unannounced inspections provide a reassurance to Ministers and to the public that nothing can be completely hidden in prisons. In practice they may not reveal much that would not have been discovered were the inspection announced; but the introduction of such inspections is proving worthwhile.

The question is often asked, not least by prisoners "What good does inspecting do?", "what is the point?" (or, as my neighbour once asked, "why bother?"). It is possible to point to improvements which have been made directly as a result of Inspectorate reports: the closing of the dormitory accommodation in the Open Estate and the move from Sentence Management to Integrated Case Management are important examples. Unfortunately it is also possible to find examples, like the completely inadequate visit room at Aberdeen, where repeated Inspectorate concerns have made no difference. Indeed, the attacks on prison overcrowding which have characterised so much of Inspectorate activity have been unfailingly, and most frustratingly, accompanied by increases in prison overcrowding.

It may not be mere coincidence, however, that the 30 years since independent prison inspection in its modern form began have been the years which have seen unprecedented transformation in the conditions and the treatment of prisoners. These are the very things which it is the duty of the Chief Inspector to inspect. Perhaps it is the very fact that inspection takes place, rather than any particular recommendation, which is the most important contribution of the Inspectorate to improving standards. Certainly the Scottish Prison Service has long recognised that independent inspection is in their interest, even although its conclusions are not always immediately comfortable. I want to put on record the unfailing helpfulness and cooperation which I have received from the Scottish Prison Service at all levels. There has never been an exception to this experience.

It would, of course, be misleading for me to suggest that my main interest has been to be helpful to the Scottish Prison Service. My main interest and my duty has been to provide successive ministers and the public with an honest and careful picture of the reality of Scottish prisons. Others, of course, have their own views. Recently a listener to a radio phone-in programme dismissed me with contempt as "the prisoners' friend". To me that did not sound like an insult.

Better prisons in a better Scotland

In my first Annual Report I wrote: " the only way to have better prisons is to have a better Scotland." That sentence has never gone away in the last seven years. It is not a cross-section of society which can be found in prisons. Scotland's prisoners, like prisoners everywhere, are poor people. The communities which suffer most from crime are the poorest communities, and the people most likely to be victims of crime are poor people. Those released from prison will be released into poverty, inequality and social exclusion. Nearly half of all prisoners have a history of serious debt problems: one third of those reported that their debt problems got worse while they were in prison (Prison Reform Trust Bromley file). Very large numbers of prisoners have no bank account, no insurance and may not know the GP with whom they are registered. The only way to have better prisons is to have a better Scotland.

It matters to us all that we do have better prisons. It matters because only better prisons (and that means at least prisons with less overcrowding) will be able to influence the re-offending rate. It matters because prisoners are a part of our community, part of modern Scotland. It matters because the way we look after those who are in our power is an accurate descriptor of the kind of people we are. No-one has put that last point better than Winston Churchill did when he was Home Secretary. I am sure that these words, which I quoted in my first Annual Report, are the most quoted words in the world of prison reform and prison study.

The mood and temper of the public in regard to the treatment of crime and criminals is one of the most unfailing tests of the civilisation of any country. A calm and dispassionate recognition of the rights of the accused against the state, and even of convicted criminals against the state, a constant heart-searching by all charged with the duty of punishment, a desire and eagerness to rehabilitate in the world of industry all those who have paid their dues in the hard coinage of punishment, tireless efforts towards the discovery of curative and regenerating processes, and an unfaltering faith that there is a treasure, if only you can find it, in the heart of every person - these are the symbols which in the treatment of crime and criminals mark and measure the stored up strength of a nation, and are the sign and proof of the living virtue in it.

While the law does not demand it, no Chief Inspector of Prisons has come from the prison service. That "lay" tradition is meant to lessen any possible suspicion of collusion between the Inspector and the Scottish Prison Service. Inevitably it means that the Chief Inspector does not have specialist expertise. That can be a good thing, since it might allow the Inspector to see prisons with the eyes of the person in the street. But such a Chief Inspector needs professional support from people with a Scottish Prison Service background and a Civil Service background. The people working with me over the last seven years, without exception, have been people of the highest integrity and ability: and they have served me and the public extremely well.

No minister of religion has held this appointment before. No doubt people who know little of ministers of religion and their work would fear naivety and gullibility: but ministers see enough of the good and of the bad to be able to tell the difference. If there is anything particular in the background and training and experience of a minister of religion which I have tried to bring to this work it would be:

Experience of trying to listen carefully and sensitively.

Understanding that speaking must be clear and unambiguous speaking.

Commitment to dealing justly.

Determination to defend the underdog.

Hope that will not be extinguished.

And I leave this work with great thankfulness for the privilege of the last seven years.

2. Overview 2008-2009

How can progress in helping prisoners to change their behaviour be assessed? One important measure might be the preparation of prisoners for release. This has been a particular theme of inspections in 2008-2009. The Open Estate has been for years a key component of the arrangements made by the Scottish Prison Service for preparation for release. It is located on two sites, at Noranside and at Castle Huntly. The Open Estate has been the subject of some controversy: it has been suggested that illegal drugs are easy to come by inside the prison, and that it is very easy for prisoners to run away. This controversy was intensified after a prisoner failed to return from an event he had been allowed to attend outside the prison, and later committed a violent and horrible crime.

The Scottish Prisons Commission ("The McLeish Commission") was asked to investigate these concerns. The Commission declared that " Scotland also needs a well-run open estate because it is not in the public interest to release long-term prisoners from closed institutions without preparing them for release and training them for freedom."

The inspection report makes it clear that "the SPS has learned lessons about the Open Estate in the past year and has made considerable improvements. This is a decisive moment for the future of the Open Estate. Who suffers most when prisoners are released from prison not prepared for safe, decent lives in the community? It will require courage to maintain open prisons which are not full in a time of unprecedented overcrowding: but it is courage which will serve the public good."

While all preparation for release is controversial, the preparation of sex offenders for release is especially controversial. Two inspections in this past year have been particularly concerned with this matter: in Dumfries and in Peterhead. In both the conclusions are not encouraging. Sex offenders are those whom the public would want to have the best possible preparation for release. They do not get it because (a) they have to be willing participants in any programmes designed to change their behaviour and many are not willing (b) there are not enough places on such programmes for those who are willing to participate (c) fears about public safety make it almost impossible for sex offenders to be tested in community work placements and home leaves before they are released and so they are released untested.

The publication of a major thematic report Out of Sight: Severe and Enduring Mental Health Problems in Scotland's Prisons attracted significant public interest. There was interest in the prevalence of mental illness in prison - four times higher than in the population as a whole. There was interest in the good links which often exist between prisons and psychiatric hospitals. There was interest in the sad fact that sometimes, still, people with severe mental illness can leave prison with almost no links to the community awaiting them. And there was support for the main finding that Prison is not the most appropriate environment for people with severe and enduring mental health problems. Their primary need is their mental health and the appropriate place to address this is in a hospital.

Another report was the result of the inspection of three places where convicted young people under 21 years of age are held who are not in Polmont: i.e. Greenock, Perth and Cornton Vale. The conditions and treatment of the young men who were in Darroch Hall in Greenock and in Friarton Hall in Perth were found to be particularly good; but those of the young women in Cornton Vale were not. The report called for the establishment of a separate unit for women who are under 21 years of age where they do not regularly mix with adult prisoners; and for an end to the current situation in which there is not a single person at any level in the Scottish Prison Service whose sole responsibility is the custody, care or management of female young offenders.

The lot of imprisoned children has been a concern repeated often in Annual Reports. It is a great disappointment to me that it is not possible in this, the Overview of my last year as Chief Inspector, to declare that the imprisonment of under 16-year-olds has ended. However, the argument has been won, the legislation to end this sad practice is imminent, and it will be for the next Chief Inspector to welcome its abolition.

What happens to Scotland's children is such an important pointer to what happens in Scotland's prisons. On Christmas Day I met a young man in Polmont whose record of violence among the most dreadful of any young person in the country. He told me that he had not been at liberty on Christmas Day since he was 11. Two weeks before I was speaking to a psychologist who supervises a Violence Prevention Programme with long-term prisoners. She told me this: 1% of Scottish children have been in care; 50% of Scottish prisoners have been in care; 80% of Scottish prisoners convicted of violence have been in care. Year after year I have said that it is naïve to blame prisons because they cannot solve the problems of Scotland. We will only have better prisons when we have a better Scotland.

3. Summary of Inspections Undertaken 2008-2009

Establishments

HMP Dumfries

Full Inspection 28 April-2 May 2008

The basic necessities of life are provided and the quality of food is good. However, some living areas do not have natural light; some cells have unscreened toilets; arrangements for the provision of underwear are poor; and the timing of meals is poor. Some mattresses are also in a very poor condition and exercise is not provided in appropriate areas.

The prison is safe; relationships are good; prisoner escort arrangements are appropriate; and there have been no suicides since the last inspection.

Prisoners are treated with respect by prison staff.

There is good communication between the prison and the escort provider; vehicles are clean; and escort staff treat prisoners with respect.

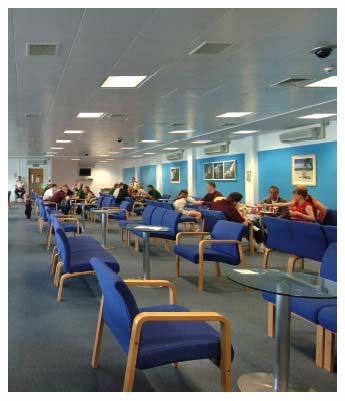

Arrangements for maintaining family contact are reasonably good: the visits room is bright, airy and spacious; facilities for visitors are good; and supervision arrangements during visits are appropriate. However, the visits booking system was not working properly and there was very little information for visitors.

Disciplinary procedures and the handling of privileged mail are carried out appropriately. However, complaint forms are not readily available in all residential areas.

All prisoners have access to learning opportunities, including those on remand and those serving short-term sentences. Around one third of prisoners participate in Learning, Skills and Employability activities.

Waiting times to see the doctor are good, and the Health Centre is clean and tidy. The addiction service generally is good. However, the referral system to the Health Centre is poor, and no appointments for healthcare are provided. Access to the dentist was very poor due to refurbishment of the dentist's room. The timing of medicine distribution at weekends is inappropriate.

Arrangements for Integrated Case Management are good; some programmes to address offending behaviour are in place; a wide range of community based partner organisations operate within the prison; and there is a well structured pre-release programme in place for long-term prisoners. However, because the sex offenders being held deny their crimes they do not participate in the " SOTP" programme which is designed specifically to address sex offending behaviour.

HMP Peterhead

Focused Inspection 3-4 June 2008

The basic necessities of life are provided although the cellular accommodation is the worst in the SPS and a form of slopping out still exists.

There are very limited opportunities to engage in purposeful work or activities.

Some small improvements have been made to the visits facility and prisoners are often able to have visits over and above their statutory entitlement. However, the visits room itself is very small and cramped and the catering facilities for visitors are poor.

There is no formal ongoing training for visit staff on child protection.

The number of prisoners completing the ' SOTP' programme, designed specifically to tackle sex offending behaviour, has increased slightly. However, there are long waiting lists and demand is not being met. As a consequence high risk prisoners may be returned to the community on completion of their sentence without having addressed their sex offending behaviour.

Some improvements have been made to healthcare provision and the service available to prisoners is now much better. Addiction services have been introduced. However, there is no full time mental health or addictions nurse and the arrangements for administering some medications gives cause for concern.

The Open Estate

Focused Inspection 15-19 September 2008

Prisoners are not exposed to harm and they report feeling safe. However, the immediate post Extended Home Leave Act2Care risk assessment is inadequate.

The system in closed establishments for assessing suitability for the Open Estate is now much more robust and at the time of inspection there were proportionately fewer short-term prisoners and more long-term prisoners preparing for release being sent to the prison. This has improved the atmosphere and reduced tensions.

The processes connected to the risk assessment and risk management of prisoners have improved considerably.

Work, Vocational Training and Community Placements are all relevant to current labour market opportunities. However, the range of education courses available is limited and there are very few prisoners undertaking literacy programmes. Arrangements to engage prisoners with literacy and numeracy requirements are not sufficiently proactive.

Extended Home Leave and Community Work Placements are the main means of reintegrating prisoners into the community. The Community Placements Scheme is excellent, but there are few opportunities for families and prisoners to prepare, together, for Extended Home Leaves. There is a lack of accredited programmes to address offending behaviour, and no "top up" programmes. Sex offenders receive the worst preparation for release.

Extended Home Leaves give prisoners significant periods of time with their families and friends. However, families are not involved in the arrangements for these. Visiting arrangements within the two sites are very good and staff are courteous, polite and helpful. There is no formal family strategy in place which encourages family involvement at induction, in addictions, or at other stages of the prisoner's stay in the Open Estate.

There has been a significant drop in the level of illegal drug taking across both sites.

The range of healthcare services is very good at both sites. However, the times at which prisoners can access these services is more restricted at Noranside than at Castle Huntly.

Whilst methadone throughcare is excellent on both sites the administration of this at Noranside falls outside recommended standards.

Relationships are in general good.

HMP Aberdeen

Full Inspection 6-10 October 2008

Prisoners report feeling safe and initial risk assessments are carried out appropriately. However, the prison is very overcrowded and there is a shortage of staff. The facilities in reception are poor.

Prisoners are treated well by Reliance Custodial Services' staff when under escort. However, the conditions in the holding rooms at Aberdeen Sheriff Court are unacceptable.

Cell windows are in a poor condition; protection prisoners have limited access to exercise; the food is poor; and prisoners do not get the same prison issue clothing (including underwear) back which they handed in to the laundry. There are often shortages of prison kit.

Prisoners are treated with respect by prison staff and relationships are good. Multicultural issues are dealt with appropriately.

The visits room is inadequate and there are no facilities for visitors or children; visits are difficult to book; there is no family policy; and the visits area is not wheelchair friendly.

Complaints forms are readily available and privileged mail is handled appropriately.

All prisoners have access to very good learning opportunities, including those on remand. High numbers participate in the education programme. However, prisoners do not have sufficient access to opportunities to work or gain work-related qualifications.

Healthcare is good, particularly in the context of the complex prisoner mix and high levels of overcrowding. However, the provision of dentistry and mental health support is inadequate, and the addiction service is struggling to meet the demands caused by overcrowding and a lack of staff. The health centre is not fit for purpose.

The prison has developed good relations with a wide range of community agencies. There are very good links with Jobcentre Plus and community employers. A good pre-release programme is in place.

HMP Edinburgh

Full Unannounced Inspection 12-21 January 2009

The new buildings provide excellent living conditions. The new reception facility is excellent and canteen provision is very good. The food is good at the point of cooking although it deteriorates when being transported to the halls. Prisoners are able to have their clothes washed every day during the week and there are good opportunities for exercise.

The prison is safe; levels of serious violence are low; there have been no escapes since the last inspection.

Relationships between prisoners and staff are very good; but there was little evidence of informal contact in prisoner areas of halls.

Prisoners are treated well by escort staff. Conditions in Edinburgh Sheriff Court are good. Conditions in Linlithgow Sheriff Court are poor.

The visits room is spacious and bright; prisoners book the visits; a number of family initiatives are in place and the Visitors Centre is a very good facility. However, there are no facilities for children in the visits room and the system for getting visitors from the Visitors Centre to the visits room is inadequate.

There are few opportunities for out-of-cell activities for remand prisoners, their accommodation is the least good, and their recreation facilities are poor.

Disciplinary procedures are fair and open. Conditions in the segregation unit are good. Complaints forms are not readily available throughout the prison.

Chaplaincy services are well developed, active, and integrated into the prison regime.

Very few prisoners go to work: the workshops are often empty.

There is very little available to prisoners at weekends.

Learning, Skills and Employability provision is good. Prisoners have good access to a wide range of learning opportunities, and receive high quality teaching and support.

The provision of healthcare is good: facilities are excellent, although underused, and there is a developing mental health service. The referral system to see the doctor is not working effectively.

The prison has developed excellent links with community-based organisations.

Other Reports

Out of Sight: Severe and Enduring Mental Health Problems in Scotland's Prisons

Thematic Inspection 2008

The main focus was as follows:

This was a thematic inspection focusing on "severe and enduring" mental health problems of prisoners in Scotland. This includes prisoners with a formal diagnosis of a severe and enduring mental health problem, and those who have not been diagnosed, but whose behaviour indicates that they experience such problems, or who suffer substantial disability as a result of their problems.

The main findings were as follows:

A very large proportion of prisoners have some form of mental health problem. Of these, only a small proportion have severe and enduring mental health problems. At least 315 prisoners with severe and enduring mental health issues were identified by prisons (not counting Polmont where psychiatrists do not diagnose young people). A further eight prisoners were identified who were, at the time, undergoing assessment in a hospital facility. Excluding Polmont, this represents around 4.5% of all prisoners. This is a much higher proportion than in the population as a whole.

The number of prisoners with severe and enduring mental health problems appears to be rising, although it was not clear if the numbers themselves are increasing, or if the visibility of mental health problems is increasing.

The most common types of severe and enduring mental health problems in Scottish prisons are schizophrenia and bi-polar affective disorder. There is also a significant number of prisoners with a personality disorder. The majority of prisoners with mental health problems also have substance misuse issues.

Prisoners with severe and enduring mental health problems have an impact on the general running of an establishment, with this group seen as being both resource-intensive and a cause of disruption. There is also an impact on prison staff, in terms of the physical and emotional demands of being required to manage difficult behaviour and respond to complex needs.

The impact on other prisoners is general disruption; disproportionate use of staff time; less access to facilities; and a charged atmosphere.

The fact and nature of imprisonment itself does real harm to people with severe and enduring mental health problems.

These impacts are exacerbated by overcrowding.

Reception and induction processes can provide the first opportunity to identify mental health needs. During a sentence, the main ways of identifying mental health problems are through observation by prison staff, other workers, prisoners, and through self-referral.

There are a number of gaps in the identification of mental health problems and needs. These include: problems with the transfer of information from courts and the community; difficulties for prisoners in disclosing issues; problems with processes and operational issues; and problems with staff being able to identify issues. These difficulties can mean that some prisoners with severe and enduring mental health problems may not access assessment and referral.

Once prisoners have been identified as having severe and enduring mental health problems which do not require transfer to hospital, the treatment which they receive in prisons generally includes: medication; access to a psychiatrist; and input from a mental health nurse.

Segregation units and separate cells are used at times, with difficulties faced in making distinctions between mental health and behavioural or management problems. The use of segregation as a response to mental illness is wrong.

The provision of advocacy support varies. In some prisons, there was no provision, or it was virtually non-existent. Prisoners generally had no awareness of their right to access advocacy support under the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003.

A number of concerns were expressed with aspects of existing provision including variations and gaps in practice and treatment; issues with medication; issues with the use of segregation; a lack of an holistic approach; a lack of day care facilities; a lack of "talking treatments"; the removal of in-patient facilities; and issues relating to overcrowding, staffing, information and other resources.

Prisoners diagnosed with severe and enduring mental illness and requiring transfer to hospital may wait longer than similar people in the community.

The referral, assessment and transfer processes are generally appropriate.

In most hospitals, the number of prisoners forms a very small proportion of the total number of patients, although this is larger in the medium and high secure facilities. These patients have access to a range of treatment, interventions and support, which are generally the same as that available to any other patient, but in the main are not available in prisons.

Unlike prison, advocacy is available in all of the hospitals visited, and some hospitals have an advocacy service on-site.

Prisoners face a range of issues prior to release, and accessing support is very important. Some work is being carried out in prisons to assist prisoners in preparing for their release and in accessing support, but the nature of this varies, particularly in relation to the level of formalised planning undertaken. A more systematic, formal, process for making arrangements to prepare people for return to the community and to ensure that their care continues is in place in hospitals.

In many cases, prisoners being released from prison have to approach organisations in the community at their own instigation, with limited external support available. Some prisoners with severe and enduring mental health problems are released from prison with few if any links to continuing support in the community, and without any arrangements for the continuation of any work which had started in prison.

There is a number of perceived difficulties in securing access to services upon release, such as GP services, hospital services, housing services, and issues for some specific groups. There are difficulties in gaining access to an in-patient bed when this is required. There are also issues relating to geographical variations and capacity of services, as well as a lack of communication between agencies.

The level and nature of healthcare staff, and particularly mental health specialist staff varies widely across prisons. Generally, nursing teams are available on a weekly basis, although there is little or no mental health nursing cover on-site overnight or at weekends. Most prisons have access to a psychiatrist, although for a relatively small number of hours.

There is concern about the level of specialist staffing resources available, the number of competing priorities, and the extent to which existing arrangements have sufficient resilience to cope with, for example, a member of staff leaving, or periods of sickness.

In all prisons, residential and operational staff have a less well-defined, but still important, and increasing role, to play in relation to prisoners with severe and enduring mental health problems. A number of concerns were raised that staff: lack specific training; may lack confidence; may feel that they have not had sufficient guidance; may have insufficient time to interact with prisoners; and may lack information about the prisoners' problems and the impact of any steps they take in working with them.

Healthcare beds have been phased out in virtually all prisons, which has given rise to concerns both within prisons, and among NHS staff. This means that more prisoners who might have been located in these beds are now located in halls.

There is some positive work taking place with prisoners with severe and enduring mental health problems, despite some of the difficulties and constraints. There have been developments to the services available in prisons, in terms of the basic care provided, the overall approach to mental health, and conditions for prisoners. There have also been changes in local and regional secure mental health facilities, in terms of the composition of the overall forensic estate.

Progress has been made in terms of throughcare, and in the development of improved communication with external organisations.

The level of understanding of mental health issues in prisons has increased, and the knowledge and awareness amongst some officers has also increased.

The stigma associated with mental health problems has reduced, both inside and outside prison, but it still remains a major problem.

The main conclusion was as follows:

Prison is not the most appropriate environment for people with severe and enduring mental health problems. Their primary need is their mental health and the appropriate place to address this is in a hospital.

Young Offenders in Adult Establishments

Inspection November 2008

This was an inspection of the conditions in which young offenders are held and the treatment they receive in Friarton Hall in HMP Perth, Darroch Hall in HMP Greenock and Bruce House in HMP Cornton Vale.

Young offenders in all three locations are safe and suicide risk management is handled well.

Relationships between staff and young offenders are generally good.

The conditions in Friarton Hall are good although Darroch Hall needs to be refurbished. The conditions in Bruce House are poor.

Access to toilets during certain parts of the evening in Bruce House is unacceptable.

The young offenders in Friarton and Darroch have a much more useful, stimulating and productive day than the YOs in Cornton Vale, and indeed than the YOs in Polmont.

The arrangements for catering are very good in Friarton and excellent in Darroch, but are very poor in Bruce. The experience of eating in Friarton and Darroch is very pleasant, but most unpleasant in Bruce.

Arrangements for maintaining family contact are good and there is evidence that this is particularly enhanced in Darroch as a result of the young offenders being located closer to their families.

Work opportunities are excellent in Friarton and in Darroch, but poor in Bruce. A number of prisoners in Friarton are also participating in community work placements which is good preparation for release. There are very few other out of cell activities available in Bruce House.

A wide range of learning opportunities in all three locations is focused appropriately on needs. High numbers participate in education in Darroch and Friarton.

The provision of healthcare in Darroch and Bruce is as good as that received by adult prisoners. The lack of an onsite and timebound service in Friarton gives cause for concern. Young offenders in Friarton do not have access to supervised medication.

All three locations have established excellent links with community organisations who contribute greatly to the reintegration process. There are no YO specific offending behaviour programmes.

When staff are focused on, and have an interest in, a particular group, then that group is better off - particularly if it is in a smaller unit close to families.

The experience of female young offenders in Cornton Vale is not good. There is very little for them to do and they consistently mix with adult prisoners in various circumstances.

A smaller unit, specifically for women under 21 years of age should be considered.

4. Review of the Prison Inspectorate's Year 2008-2009

Inspections and Other Reports

Inspections for the year were completed as follows.

Full Inspections

|

HMP Dumfries |

28 April-2 May 2008 |

|

HMP Aberdeen |

6-10 October 2008 |

|

HMP Edinburgh |

12-21 January 2009 |

Focused Inspections

|

HMP Peterhead |

3-4 June 2008 |

|

The Open Estate |

15-19 September 2008 |

Other Reports

|

Out of Sight: Severe and Enduring Mental Health Problems in Scotland's Prisons |

2008 |

|

Young Offenders in Adult Establishments |

November 2008 |

Submission to the Scottish Parliament

The 2007-2008 Annual Report was laid before the Scottish Parliament on 5 November 2008.

Staff

|

March 2009 |

April 2008 |

|||

|

HM Chief Inspector |

Dr Andrew McLellan |

(F/T) |

Dr Andrew McLellan |

(F/T) |

|

Deputy Chief Inspector |

John T McCaig |

(F/T) |

John T McCaig |

(F/T) |

|

Assistant Chief Inspector |

Dr David McAllister |

(F/T) |

Dr David McAllister |

(F/T) |

|

Inspector |

Karen Norrie |

(F/T) |

Karen Norrie |

(F/T) |

|

Personal Secretary |

Janet Reid |

(F/T) |

Janet Reid |

(F/T) |

A list of Specialist and Associate Inspectors for the year is provided below.

HMP Dumfries

|

Nick Welsh |

Associate Inspector |

|

John Bowditch |

Education Adviser |

|

Stewart Maxwell |

Education Adviser |

|

Andrew Brawley |

Education Adviser |

|

Social Work Inspection Agency |

Social Work Adviser |

The Open Estate

|

Jan Clark |

Associate Inspector |

|

Peter Connelly |

Education Adviser |

|

Donnie Macleod |

Education Adviser |

|

Social Work Inspection Agency |

Social Work Adviser |

HMP Aberdeen

|

Sandra Hands |

Associate Inspector |

|

Stewart Maxwell |

Education Adviser |

|

Jim Rooney |

Education Adviser |

|

Social Work Inspection Agency |

Social Work Adviser |

HMP Edinburgh

|

Iain Lowson |

Education Adviser |

|

Karen Corbett |

Education Adviser |

|

Social Work Inspection Agency |

Social Work Adviser |

Young Offenders in Adult Establishments

|

Donnie Macleod |

Education Adviser |

|

Jim Roonie |

Education Adviser |

Finance

The Inspectorate's budget for 2008-2009 was £335k. Of this:

|

Staff costs for five full-time staff |

£308k |

|

Advisers, training, travel and subsistence and other running costs |

£27k |

Communications

Recent reports can be found on our website ( www.scotland.gov.uk/hmip).